Non-Malay response to Malayan Union

In contrast to the widespread, spontaneous and highly impassioned Malay opposition to the Malayan Union proposals, the non-Malay response was decidedly lukewarm and maybe even indifferent. The reason for this was twofold.

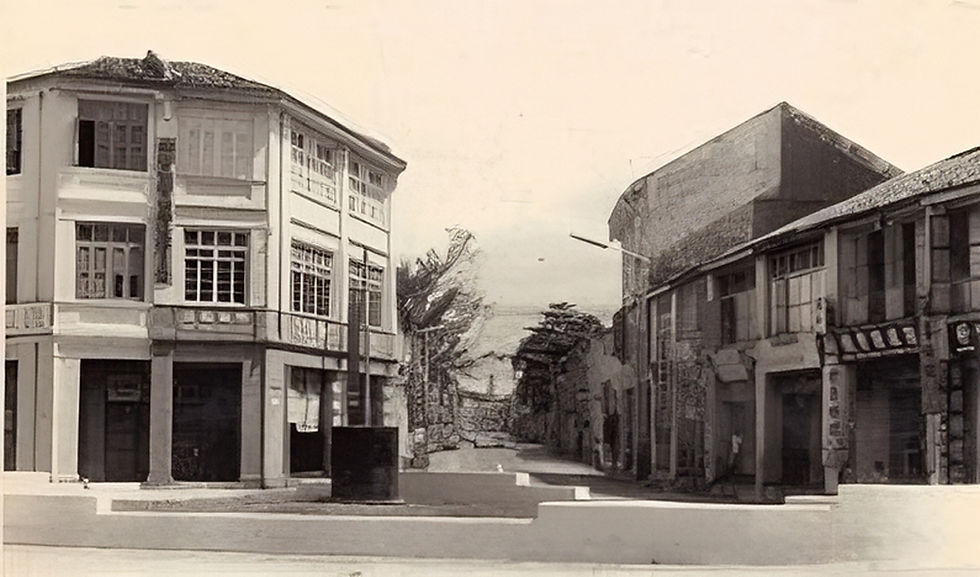

For one thing, many Chinese were focusing on rebuilding their lives after the war. The lives of the Chinese were severely disrupted during the war, a situation not mirrored in the lives of Malays. While most Malays lived in villages where the Japanese only occasionally ventured, almost all Chinese lived in towns, where they were subject to much harassment from Japanese soldiers. And the Japanese largely saw the subjugated Chinese Malayans as extension of the Chinese in China against whom they have been fighting for much of a decade. Many Chinese businesses shuttered as it was difficult to run businesses under such conditions and that added to the depressing environment in the largely Chinese towns. During the war period, many Chinese moved closer to the jungle to avoid harassment by Japanese soldiers and the constant demands for collaboration. This had the effect of leaving Chinese villages vulnerable to the Communist insurgency later during the Emergency, which in turn led to the Briggs Plan that moved most Chinese villagers into new villages, vestiges of which are still evident today.

With the end of the war, the Chinese moved back to towns to reclaim their homes, and to restart their businesses and livelihoods. For instance, Chinese leaders such as Tan Cheng Lock and HS Lee spent their war years in India and China respectively and on returning to Malaya, both had a lot of business interests to settle and rebuild. The conditions were made worse during the British Military Administration period as there was little security and economic stability that they were used to before the war. With the Malayan Union proposals being published less than six months after the British re-occupation, one can understand why the Chinese community had little attention to spend on it.

Politically, the Chinese and the Indians were also less interested in how a British polity is to be re-organised as both communities would have preferred straight independence. This was in line with the anticolonial sentiments current in both China and India, albeit in different forms. This differed from the Umno-organised protests, which was aimed not at independence but at restoring the position of Malays, which Malayan Union was seen to have eroded.

There were non-Malay orgganisations which did have the capacity and interest to evaluate the Malayan Union proposals. The Malayan Democratic Union (‘MDU’), largely composed of English-educated left-wing intellectuals based in Singapore, and the Communist Party of Malaya (‘CPM’) both wanted Singapore to be included in the Malayan Union but for different reasons. The MDU saw Singapore as an extension of Malaya, a view that was common on both sides of the Causeway at that time. Many Singaporeans and Malayans considered the enforced divorce as traumatic since it imposed a border that never existed in all of history until then. Many Malayans in the peninsular, Chinese and Malays alike, moved to Singapore to find a job and seek their fortune, very much like Americans moving to New York. In fact, many Malays launched their artistic careers in the thriving entertainment scene in Singapore, such as the P Ramlee did in 1949. The CPM on the other hand probably wanted the inclusion of Singapore in order to maintain the ethnic Chinese majority in British Malaya.

British response to Umno protests

As a result of the Umno protests, the British colonial administration entered into negotiations to revise the Malyan Union proposal through a committee of 12, comprising six British officers, four representing the Malay royalty and two representing Umno. The key negotiators on the Malay side was Umno, whose lead the Malay royals would follow. The royals have lost much credibility for signing the MacMichael treaties and though they still received the traditional obsequeince from Malays, they were well aware that the Malay streets belonged to Umno.

The British chose to negotiate with the Malays for legal and political reasons. Legally, the British see themselves as being in Malaya at the request of the Malay rulers and the treaties with the Malay rulers were the legal basis of their presence in Malaya. Therefore, any reorganization of the government would require amendments to those treaties, which was signed solely with the Malay rulers.

Politically, it is understandable that the British pro-Malay policies in Malaya gave priority to Malay sentiments as the British understood it as their mission to be in Malaysia to develop the Malays. The British were also haunted by the violence of the anticolonial uprising in Indonesia, happening at that time. The British had a hand in putting down the uprising, given the weakness of the Dutch government just emerging from German occupation during the war, and so, saw firtshand the destruction in Bandung and elsewhere. Both the British and the Malay ruling elite therefore had an interest in avoiding an Indonesian scenario all together.

As with the common Malay view at that time, many British administrators continue to see the Chinese and Indian workers as transient workers who would return to their respective ‘homelands’ once they have made their prosperity. And indeed, many Chinese and Indians did make the journey back and forth between Malaya and their respective legacy countries. And indeed, many Chinese Malayans did work in China at one point in their lives and many also served in the Chinese government, both under the dying Manchu Dynasty and under the Kuomintang nationalist government. At the time of Malayan Union, the Civil War in China was still raging and the communists have not yet taken over as the government there and thus, China has not yet closed its doors: people were still free to come and go. Similarly, India was part of the British Empire and later, the British Commonwealth, and there was still free entry for Indian Malayans.

The other feature of these negotiations was that it was held in secret. This was probably to lower the political temperature at that time. Secret negotiation give space to negotiators to negotiate on more considered basis without the constant intervention of an under-informed public. Of course, this gave rise to a lack of transparency which in turn gave rise to suspicions on the part of those not involved in the secret negotiations. This is when the non-Malays and the left-wing Malay organisations started to respond. The suspension of the citizenship provisions in the Malayan Union Constitution made the Chinese realise what they have lost and all support for Malayan Union among the Chinese evaporated. It also gives them an impetus to be at the negotiating table to protect the citizenship aspirations of Chinese Malayans, more than half of whom at that time were born in Malaya.

Response to the Anglo-Umno secret negotiations

The prime mover of the opposition to the secret negotiations was Tan Cheng Lock, the President of the Straits British Chinese Association, which while drawing its membership from Penang and Malacca, was the most advanced political voice for Chinese Malayans, and an English-speaking voice at that. There wasn’t that many organisations at that time with the intellectual and organisational capacity to oppose the negotiations so it took quite some time before a meeting between opposition organizations was held on 19 November 1946.

It was likely organised by Party Kebangsaan Melayu Malaya (Malaya Malay Nationalist Party ‘PKMM’) and endorsed by Tan Cheng Lock, although he was not present at that meeting. It was attended by representatives of the CPM, MDU and PKMM. The meeting adopted three principles telegraphed in by Tan:

· A united Malaya including Singapore

· Popularly elected Federal and State legislatures

· Equal citizenship rights to all who made Malaya their home

‘To all who made Malaya at their home’ became very much a phrase for the Jus soli proposals, into which the third principle evolved. Jus soli is a legal principle meaning right of soil. It means that anyone who was born in that country has an automatic right to citizenship. One country that practices this today is the United States, where anyone born on American soil is an American citizen even if their parents were there illegally. This contrasts with Jus sanguinis, which means right of blood. Under Jus sanguinis, a person claims citizenship based on their parentage where ever they are born or are residing. For instance, anyone with Japanese or German ancestry could claim Japanese or German citizenship at any Japanese or German embassy anywhere in the world. Most countries today, including Malaysia, operate citizenship laws that fall between both these two extremes.

AMCJA and the alphabet soup

On 14 December 1946, a meeting organized by the MDU in Singapore led to the formation of the Council for Joint Action (‘CJA’). By year-end, the CJA had an expanded membership of

· SBCA,

· MDU,

· PKMM,

· Malayan Indian Congress (‘MIC’) (Yes, the first major action of the newly-formed MIC was to oppose Umno!)

· Trade unions in Singapore: Singapore Federation of Trade Unions (‘SFTU’), Singapore Clerical Union

· Trade unions in Malayan Union: Pan Malayan Federation of Trade Unions (‘PMFTU’), Clerical Unions of Penang, Malacca, Selangor and Perak,

· Organisations in Singapore: Singapore Chinese Association, Singapore Indian Chamber of Commerce, Singapore Tamil Association, Singapore Women's Federation

· Organisations in Malayan Union: Selangor Indian Chamber of Commerce, Selangor Women's Federation, Malayan New Democratic Youth's League, Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Ex-Comrades Association (‘MPAJA EA’) and Peasant's Union

A follow-up meeting later that month in Kuala Lumpur evolved the CJA into the Pan-Malayan Council for Joint Action (‘PMCJA’). Tan Cheng Lock was elected chairman with MDU’s Gerard D’Cruz as the secretary general. The PMCJA eventually change its name to the All-Malayan Council for Joint Action (‘AMCJA’) in August 1947.

This multiple changes of name was reflective the broad nature of the coalition that attempted to bring all organizations opposed to the Anglo-Umno negotiations under a single umbrella, each having its own separate objective. You can see from this list that it included many of the key non-Malay ethnic or cultural organisations at that time as well as many left-wing trade unions, ranging from proxies of the CPM (SFTU and MPAJA EA) to the Englishmen of the SBCA. Essentially, it was a joint action committee of strange bedfellows to coordinate activities. The name of PMCJA came in when PMFTU joined but Chinese businessmen didn’t like the Pan-Malaya part of the name, seeing it as communist. That is why the name changed to All-Malaya - by then, Chinese businessmen were secured as funders of the movement.

You may also have noticed that there was no Malay organisations in the list. This is because to the Malay mindset, Malaya was a British construct and so, to the Malays, Malayans referred to all those people brought in by the British: the Chinese and the Indians. Malays were not seen as Malayans. That is why the Malay name for the Federation of Malaya was not Persekutuan Malaya but Persekutuan Tanah Melayu. So, there is also a racial perception issue which indicates that even among such progressive Malayan thinkers, it is still a long way from thinking as a single

country. As a result, Malay organizations set up their own umbrella group called the Pusat Tenaga Rakyat (Centre for People’s Power, ‘PUTERA’) on 22 February 1947 with the following initial membership:

· PKMM

· Angkatan Pemuda Insaf, led by Ahmad Boestaman

· Angkatan Wanita Sedar

· Gerakan Angkatan Muda, led by Aziz Ishak

· Barisan Tani Malaya

· Majlis Agama Tertinggi Se-Malaya

PUTERA eventually had 29 member organisations.

Thus, was born the PUTERA–AMCJA coalition, the final iteration for what is essentially a working committee. (OK, it was actually born PUTERA–PMCJA and only became PUTERA–AMCJA in August 1947 when PMCJA became AMCJA.) I find this alphabet soup interesting because it indicates that the Malaysian love for abbreviations today went back as far as then. For simplicity, I will just refer to it as PUTERA–AMCJA throughout. (Sidetrack: Did you know that the longest abbreviation in the Guiness Book of World Records was Malayan: it was so long that the abbreviation was abbreviated, to five letters.)

Some PUTERA leaders, like ex-KMM stalwarts Boestaman and Aziz, became prominent in Malayan political life. Boestaman consistently demanded total independence from the British and never made accommodation with Umno whom he considered British collaborators. To this end, he eventually founded Parti Rakyat in 1955, which eventually merged with Keadilan to form Parti Keadilan Rakyat (‘PKR’) in 2003, which first became part of a ruling coalition in Malaysia in 2018. Aziz Ishak was the brother of Singapore’s first President, Yusof Ishak, and became one of the few KMM cadres who joined Umno. He eventually became a minister before resigning in 1963 - or was pushed out - finding no place for an egalitarian socialist in an increasingly capitalist Cabinet.

People's Constitution

Immediately after the Singapore meeting, a letter of protest was sent to London on 16 December 1946, which outlined the intention of PUTERA–AMCJA to boycott the impending Anglo-Umno proposals to replace Malayan Union. The Anglo-Umno proposals themselves were published on Christmas Eve 1946 as a white paper ostensibly intended to garner comments from the other communities.

The results of the Anglo-Umno negotiations resulted in the following agreed points

A Federation of Malaya to replace the Malayan Union, comprising nine peninsular states, Penang and Malacca

A central government comprising a High Commissioner, a Federal Executive Council and a Federal Legislative Council

In each Malay state, the Government shall comprise the ruler assisted by a state Executive Council and a Council of State with legislative powers. In each of the Straits Settlements, there will be a Settlement Council with legislative powers.

A Conference of Rulers to consult with each other and with the High Commissioner on state and federal issues.

Defence and external matters will be under British control.

Rulers would undertake to accept the advice of the High Commissioner in all matters relating to government, but would exclude matters relating to Islam and Malay customs.

Legislative Council comprising the High Commissioner, three ex-officio members, 11 official members, 34 unofficial members including heads of government in the nine states and two settlements and 23 seats for representatives of industries etc

UMNO and Sultans would agree to this only following the scrapping of the MacMichael treaties.

One can see from the above that much of the current government structure we have - Council of Rulers, state exco, etc - date from this Anglo-Umno agreement.

The Australian commissioner at that time (commissioner means ambassador) reported to Canberra that the agreement will be opposed by non-Malays who felt they were not consulted. Whether the British administration and the Umno leaders intented to accept pan-communal considerations was questionable.

The response of PUTERA–AMCJA though, was clearly negative, seeing the new constitution as discriminatory to non-Malays and would delay the elections & independence they all demanded immediately. PUTERA–AMCJA worked to organise demonstrations across Malaya from the new year to protest the proposals. On 10 August 1947, PUTERA–AMCJA expanded the original three principles into its own counter-proposals, a full-blown constitution based on the following ten principles:

A united Malaya including Singapore

Popularly elected central, state and settlement legislatures

Malay constitutional rulers will govern through democratic state councils

Special measures for political and economic advancement of Malays

Customs of Malays and Islam fully controlled by Malays through a special council

Equal citizenship rights for all who made Malaya their home

Malay should be the sole national language of Malaya

Defense & foreign affairs be a shared responsibility between Malayan & British governments

The nationality is Malay - I have explained this clause in the first article of the series

The colours red and white must be included in the composition of Malaya’s national flag

The differences with the Anglo-Umno constitution can be summarised as follows:

People's Constitutional Proposals | Revised Constitutional Proposals |

A united Malaya including Singapore | A federation of the Malay states and the former Straits Settlements excluding Singapore |

Popularly elected central, state and settlement legislatures | An appointed Executive Council headed by a British High Commissioner (a person higher than the Governor and recognises a certain level of autonomy, but it really was a change in title with no change in substance) in Malaya and an appointed Federal Legislative Council of 52 members, amended from the intial proposals. |

Equal citizenship rights for all who made Malaya their home and the object of their undivided loyalty | Automatic citizenship only for subjects of Malay rulers, people who identified as Malays and British subjects born in the Malaya/Singapore or had lived there for 15 years. Anyone else can apply if they had lived in Malaya for 8 of 12 years (if born in Malaya/Singapore) or 15 of 20 years (if otherwise) |

Malay Rulers to have real sovereign power responsible to the people through popularly elected Councils | Malay Rulers recognised as sovereign monarchs with inherent prerogatives, powers and privileges, but still subject to the King in London and his representatives |

Malay customs and religion to be fully controlled by the Malay people through special councils | Malay customs and religion placed within the sole jurisdiction of the Malay Rulers |

Special provisions for the political, economical and educational advancement of the Malays | Special provisions for the political, economical and educational advancement of the Malays |

Malay to be the sole official language | Malay and Englishrecognised as official languages |

A national flag (already existing: see the article on Malayan flags) and anthem | A national flag was to be adopted (and only adopted from 1950) with no provisions for a national anthem |

Melayu to be the title of any proposed citizenship and nationality in Malaya | No provisions for a Malayan nationality was adopted but a distinction was made for the first time between Malayan and Singaporean citizens |

Foreign affairs and defence to be the joint responsibility of the government of Malaya and the government of Great Britain | All portfolios remained within the prerogative of the British High Commissioner and the British government (The British retained the finance and defense portfolios even in the first Tunku Cabinet in 1955, until independence in 1957) |

A Council of Races to be set up to block any discriminatory legislation that is based on ethnicity or religion | No such provisions were provided for |

Anglo-Malay sovereignty entrenched with the provision of a Conference of Rulers consisting of the Malay rulers presided over by the British High Commissioner, and a 55% reservation of Malay representation in the Federal legislature for the first three terms (Malay proportion of the Malayan population, including Singapore, at that time was about 38% - less than Chinese alone) | A Conference of Rulers was formalised. Ethnic representation in the Federal Legislative Council appointed by the British Commissioner was set with no provisions for an elected legislature |

On 21 September 1947, the People’s Constitution was publicly presented for the first time in front of a crowd of 20,000 in Singapore. It called for the establishment of a royal commission to revise the Anglo-Umno constitutional proposals. This was rejected out of hand by the colonial authorities. The authorities did not want to undo all their hard work of renegotiation with Umno. They had backed down once but backing down a second time would make it a hard habit to break. But in doing so, they chose sides and had cast the die on how the social and political life of the country was to be cast for the next three generations even before the country was born.

Hartal

Still, the People’s Constitution marched on: copies were printed and disseminated throughout Malaya and Singapore, with copies sent not just to the colonial government in Kuala Lumpur but also to the Prime Minster and the Colonial Office in London. Demonstrations intensified until a successful strike was organized in Melaka and Ipoh to press PUTERA–AMCJA demands. The success of the strike led to a decision to hold a nationwide strike. PUTERA–AMCJA issued the Hartal Manifesto on 6 October 1947, calling upon all who make Malaya their home to stop work for a day. The date chosen was 20 October 1947, the date the British parliament was set to open to discuss, among other things, the negotiated Anglo-Umno constitutional proposals.

The strike, called the Hartal, was financed by the Associated Chinese Chamber of Commerce (‘ACCC’), the group representing Chinese businessmen. This was the group that had the financial clout to make a difference to the success of any anti-Anglo-Umno resistance to the proposals. The strike was widely publicized throughout Malaya by use of flyers and posters. And, on 20 October 1947, the streets in towns throughout Malaya and Singapore went quiet as a reported 140,000 workers throughout the country downed their tools. If you think that the pandemic was the only time that the streets went quiet in Malaysia, you are grossly mistaken: almost all the offices and shops in almost all towns were closed, with the exception of government offices.

There were some localized resistance in some areas, notably Batu Pahat out of loyalty to Onn Jaafar, their one time District Officer. There were some isolated disturbance reported in Bagan Datoh and Penang. While the success of the strike was undeniable, one should caution that it is not as widespread as has often been depicted. It was largely an urban phenomeneon, publicized very much among the more progressive thinking Malayans in towns and among the non-Malays in rural estates and mines. There was little evidence that the strike penetrated into the more rural villages where conservative Malays lived. Most Malays were not workers, being self-employed farmers and so most had no employers to strike against. As a result, the majority of the Malays were untouched by the strike.

Successful as it was, the strike did not achieve its aims as the British colonial administration chose to ride out the storm rather than to renegotiate the entire constitutional proposals, especially on the much more radical lines proposed by PUTERA–AMCJA. The PUTERA–AMCJA proposals were unlikely to find agreement among the more conservative Malays, especially outside of the Malay ruling elite.

A second strike was planned on 1 February 1948, the date that Federation of Malaya was to be inaugurated, but because of lukewarm support from the ACCC which funded the first strike, the second strike was called off. One must remember that the ACCC was set up by Kuomintang party members, in part to fund and to organize support for the nationalist cause in China. The strikes coincided with the time when the nationalists were starting to lose the civil war in China, and there were calls for more funding to the support the war effort, leaving less for local Malayan activism. Also, Chinese businessmen and employers were uneasy with cooperation with communist proxies and trade unions.

The calling off of the second strike and the inauguration of the Federation of Malaya, over the opposition by PUTERA–AMCJA had a big impact on the morale of the opposition and halted its momentum. The final nail in the coffin was the declaration of the Emergency in June 1948 and many of the left-wing leaders and trade union leaders in the PUTERA and AMCJA were incarcerated. Many of the organisations withdrew, went underground or dissolved itself and eventually both PUTERA and AMCJA withered and eventually ceased to exist.

Conclusion

The 1947 All-Malaya Hartal was a landmark event in the struggle for independence in Malaya, but not because it was a success: on the contraty, it failed miserably in its aims. Despite the progressive aspirations of its leaders, the initiative failed to foster a unified vision of the country. It was born of collaboration between two coalitions organized along communal lines but fell short in comprehending the complexities of a nation bridging communal and ideological divides. Just as the Chinese businessmen was unable to fathom the non-commercial aspirations of the Malay left-wing activists. Many left-wing Malay intellectuals themselves have little patience for what they considered the backward views of rural Malay conservatives, who formed and still forms today, the majority of their community.

But, it was landmark because it was the first time different communities in Malaya came together for a common vision of independence for their country. A full five years were to pass before the Alliance was formed, with its intially hesitant commitment to independence. The Hartal was only a nascent move and though many lessons emerged, it would be a long struggle on the road to create a single nation and a single thinking out of these disparate communities. And that struggle continues on very much to this very day largely because the lessons emerged were never fully learnt. The next step in the struggle to build a single nation will be discussed in the next article.

Comments