15 - Races working together

- Jim Khong

- Feb 29, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Mar 8, 2024

The first five months of 1948 was a rather good period for Umno. The Federation of Malaya was set up on February 1 with a constitution negotiated between them and the British. The second Hartal failed, leaving the opposition to the Anglo-Umno front in disarray and in an indecisive mood unsure of how to proceed. June 1948, though, saw the start of the Emergency, a war that would drag on for a good 12 years.

Effect of the Emergency on inter-communal relationships

I would not go into details of the Malayan Emergency but would only discuss the impact that it had on inter-racial relationships in Malaya and its effect on the road to independence. The first reaction of the British was to arrest most of the left-wing leaders, whether or not they were communists. This left many left-wing organisations, Malay and non-Malay alike, bereft of leadership and most eventually faded away through inaction. This left the independence struggle largely in hands of the more conservative wing of Malayan society .

The second effect of the Emergency was rooted in British experience from their colonial wars. The British did plenty of suppressing native uprisings in the past one century, particularly in the Middle East and Africa. One major lesson they took away from all this was that suppressing natives was not just a military effort, but required both statecraft in providing a political edge to their native supporters as well as diplomacy in splitting the opposition. By the time of the Malayan Emergency, the British had both down to a fine art. This explains British success in the Malayan Emergency as opposed to the abject American failure in Vietnam two decades later.

British strategy

The British realised that political support in fighting the Communist was dependent on some form of progress towards Malayanisation of the government, with a path to independence dangled before the populace. The British would prefer to leave any independent Malaya as a country with equal citizenship and, if led by Malays, had a clear role in place for the Chinese and Indian minorities in a new country.

This is where the British belatedly realised that their previous light-touch approach to governing Malaya, both under the commercial interests of the British East India Company and under an over-stretched British Colonial Office, was not conducive to a non-communal approach to politics in Malaya. Still, they put their minds to undoing their century-old policy of minimising problems between races by keeping the races apart. In this, they were successful, with the help of equally far-sighted Malayan leaders.

On the other hand, splitting the opposition was easy: it largely involved forcing Chinese Malayans to choose between them and the Communists. They understandably avoided making loyalty to the British crown as the alternative to the communists but rather the maintenance of a thriving business environment within the context of a Malayan polity in which Chinese would have a role.

That was the third effect of the Emergency: the pressure on the Chinese community to choose sides in the conflict, in particular the Chinese business community. Conservative Chinese businessmen were natural anti-Communist, but they had to cooperate with the British with whom they had an ambivalent relationship. On one side, the Straits Chinese were rather close with British authorities, with ties going back more than a century since the British established themselves in Penang and Singapore. On the other side were the more recent Chinese arrivals, who inherited mistrust of the British from the Opium Wars back in China. As such, traditional Chinese Malayans tend to be anti-colonialists, both conservative and Communist alike. This made the Chinese business community uneasy partners to the British in the anti-Communist war.

Getting the more conservative Chinese to work with the British even if reluctantly, saw the rise of English-speaking Straits Chinese through their role as intermediaries. Straits Chinese became leaders of the Chinese community as they were the only ones who can work with and were trusted by both the British and conservative Chinese, and often speaking both languages.

British promotion of multi-culturalism

It should be noted that the British desire to leave Malaya to a multi-communal government was very much driven by culture as much as by practical considerations. The British saw themselves as a culture based on fairness and in that sense, seek equality for all peoples. This is not to say that racism did not exist in the Britain or that colonial citizens were treated as equal partners, but this was and still is how the British saw themselves. To this end, the British have always preferred equal citizenship rights in an independent Malaya ever since Malayan Union. We see this in the deliberations of both the Reid and Cobbold Commissions, which we will discuss later.

The other motivation is rather more pragmatic as many Chinese and Indians Malayans were born under British rule and were therefore British subjects. Legally, only those born in the Straits Settlements were British subjects and thus under direct British responsibilities. Politically, though, it would be hard for the British to separate their responsibility to the Straits Chinese and Indians from those living in the Malay states. If the Chinese and the Indians were not to be citizens in an independent Malaya, they would be British subjects, with the right to move to the mother country. And there were some two million of them at that time.

This was what happened in the early 70s when South Asians were expelled from East Africa and were taken in by the British even though there was arguably no legal responsibility for those who were African or South Asian citizens. Furthermore, unlike the Indians in Africa, returning to a Communist regime in the mother country was not an appealing option for many conservative Chinese Malayans.

Communities Liaison Committee

The British made clear that the path to independence will involve a handover of power to a political alignment of the three communities. However, as we have seen, the accidents of British rule had obviated a sense of a single nationhood that is based on a common vision of the three communities. As a result, peoples of the three communities had little with each other in common in terms of language, culture and religion. Worse, most lacked understanding of each other’s intentions, social norms and practices. Also, the leaders and political elites in the three communities had little experience in working with each other, other than during their short-lived opposition to the Anglo-Umno front.

Henry Gurney

On 1 October 1948, Sir Henry Gurney was appointed High Commissioner to replace Edward Gent, who was killed in a car accident. Gurney had extensive experience as a colonial administrator in Palestine and British Africa. Appointed in the midst of the anti-communist war, Gurney quickly conceptualised the basic tenets of the social, economic and political side of the struggle, without which no military effort will succeed. Within a year of taking office, Gurney proposed to the Colonial Office plans for the devolution of government to Malayans, including elections starting at municipal and local levels. Coming so soon in the military war, such clear thinking was testimony of the foresight of the man,

Gurney realised that inter-communal dynamics were pulling the communities apart since the Japanese occupation while the debacle over Malayan Union and the subsequent Anglo-Umno renegotiations into the Federation of Malaya constitution certainly did not help. Gurney had to create conditions for the devolution of government to Malayans and those conditions are premised on political leaders from all communities willing to cooperate together in a single government as equals.

Gurney’s solution was multi-fronted. It included setting up a Chinese representational body that was equal in stature to Umno and I will discuss the formation of the Malayan Chinese Association ('MCA') further in the next article. It also required a structure to bring political leaders from the various communities together to give them the experience of working together and to establish the trust that was necessary for a working government. Gurney expected that this will lead to sufficient political maturity for elections as well as participation of all communities in a cooperative government.

Establishment of the CLC

Thus, on 31 December 1948, the British Commissioner-General for South-east Asia, Malcolm MacDonald met Umno president, Onn Jaafar at the latter’s house in Johor Baru with a proposal to set up a Communities Liaison Committee (‘CLC’) as a forum for to foster inter-communal dialogue and to discuss government policy proposals multi-communally. Also present at that meeting were Tan Cheng Lock, then in discussions to lead the newly formed MCA and EEC Thuraisingam, also known Ernst to his good friend, Onn. It is sad is that such a committee was necessary but it was a crucial step towards building a nation from scratch. The CLC became the successful prototype of inter-communal cooperation in Malayan governmental affairs.

On 10 January 1949, the committee was set up with five representatives from the Malay community including three from Umno led by Onn, three representatives from the Chinese community led by Cheng Lock and the chairman was to be Thuraisingam. In August, three more members were appointed to represent the Indian, European and Eurasian communities. There was no representative from the colonial administration as this was deemed something that needs to be done only by the communities who will be inheriting independent Malaya. MacDonald held the role of advisor, effectively making him the unofficial broker to this effort to initiate inter-communal governance in Malaya.

CLC success

Ultimately, the CLC did lead to several policy proposals that advanced inter-communal government, the most important of which was the member system to supersede the CLC. Essentially, the executive council was expanded from eleven to twelve to include five Malayans, thus leaving the British still in the majority and in charge of the more critical positions of Chief Secretary and Financial Secretary. Each member will have his own portfolio much like a cabinet in all but name but without the formal title of ministers, with the concomitant rights and responsibilities that such a title would imply. Most crucially, the portfolio for security was removed from the executive council and thus, from the privy of its Malayan members. It seems the British at that point still did not trust Malayans with a role in the war against the communists.

The CLC also discussed a number of other initiatives which became priorities after the member system was set up in April 1951. Onn was appointed the Member for Home Affairs, putting him responsible for his proposal to offer Malayan citizenship to non-Malays. Thuraisingam was appointed the Member for Education to implement the much-needed reforms we discussed in the previous article. Three other Malayans joined the executive council at a later stage and the Member system provided Malayans with much-needed experience in government, particularly working cross-communally.

Informal discussions

The CLC has to be understood as one of Englishmen from different racial communities. While the committee had formal meetings which resulted in various proposals, the more interesting work to me were the informal meetings, in which this bunch of Englishmen sat around presumably over tea and pipes exchanging stories from their respective communities’ experiences of inter-communal interactions (It is stereotyped and thus likely to be inaccurate but it was a lovely picture. If anything, Onn and Ernst, the two Anglophiles drank teh tarik from saucers when meeting at the latter's house.). It was the stories exchanged, away from the glare of media coverage, that promoted an understanding of each other’s communities and built the respect & relationship necessary for cooperative government. We are fortunate that many of these stories were recorded for posterity.

One particular story that struck me was one of a Malay rubber tapper who brought rubber into town one day and managed to get a good price for his work, much better than what he would normally have gotten from other Chinese dealers. The next time he returned to that same dealer, however, the price has dropped considerably and he got much less money than he expected. It turned out that when the other Chinese rubber dealers in town found out the price this dealer offered, they pressured him into complying with the normal lower price charged so that their business will be protected.

I assume stories like this were common in pre-independence Malaya and wondered whether it gave rise to the stereotype of the cheating Chinese businessmen common among some Malay circles when I was young. Of course, the story did not involve any cheating in the conventional sense of fraud or of not honouring business promises. It is more a story of abuse of a dominant economic position, in the pursuit of profit maximisation but to the detriment of business partners of other races, even if legal at that time. Of course, to that rubber tapper going home with less money than he felt he deserved, such distinction was rather moot.

CLC Contributions

I believe that the CLC made great contributions to Malayan independence. Beyond the establishment of experience and trust, the CLC also enabled the British to pull Malay and Chinese leaders together in an environment of respect for each other’s positions, ingredients necessary to negotiate and cooperate in formulating future government policies. For one thing, the CLC brought the Chinese leaders into the fold of government and more influence on government policy than they ever had in colonial Malaya.

It also moved the thinking of Umno leaders to look beyond the narrow confines of the Malay community in individual Malay states, to a single cross-communal national awareness. With it came the realisation that citizenship has to be offered to non-Malays together with a role in governing the country. As a result, Umno changed its slogan in March 1951 from “Hidup Melayu” (“Long live Malays”) to “Merdeka” (“Independence”). Interestingly, this was at the instigation of its youth wing, who were typically nationalistic Malay until today, but no doubt at the urging of Onn, who was still president at that time.

Gurney’s demise in a communist ambush in 1951 was a great loss as, in a way, Gurney’s vision crippled a communist struggle dependent on colonial failures and communal disaffections. But the chance killing came too late for the communists as Gurney managed to establish the path of our country before he died, one that became the most practical way for this country of strangers to achieve independence together.

Municipal elections

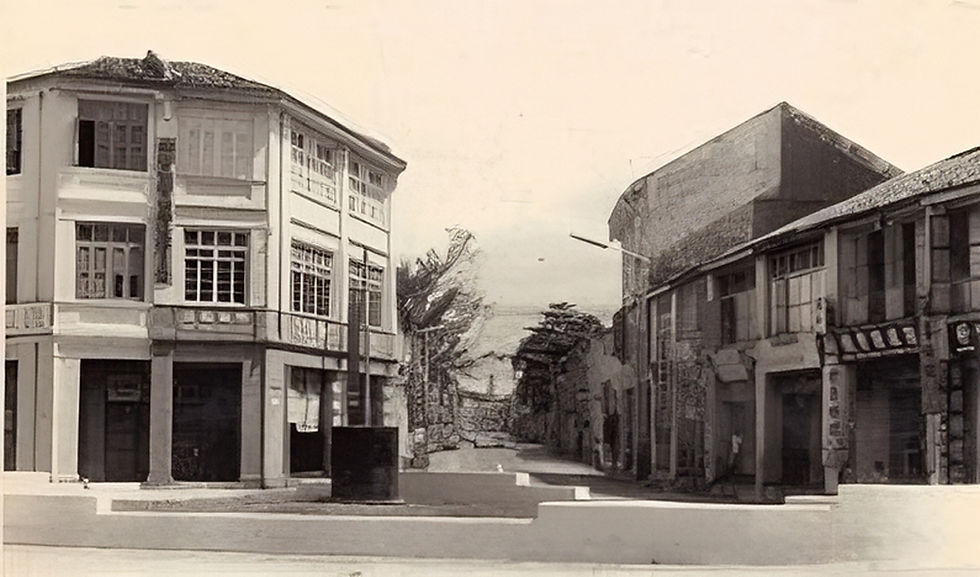

Gurney’s initial electoral plans for Malaya involved polls, first in Kuala Lumpur as the federal capital in November 1951 and the other two municipalities of Penang and Malacca a month later, followed by the larger towns in stages in 1952. In the event, the Kuala Lumpur and Melaka elections was delayed because of Gurney’s death the month before, leaving the first modern elections in Malaya to be held in Penang on 1 December 1951. Kuala Lumpur followed on 16 February 1952 while Melaka held its municipal elections on 6 December 1952 together with a number of local councils including Johor Baru, Muar, Batu Pahat and Pasir Pinji New Village in Ipoh.

Background

The 1951 municipal election in Penang was often described as the first election in Malaysia, which was not strictly accurate. The first elections in Straits Settlements were recorded in 1837 with a rather limited suffrage and British only candidates. Somehow it didn’t work out and elections were not seen again for more than a century. In any case the 1951 election in Penang had little impact on the rest of the country as the politics of Penang were specific to it and most parties were local, not national.

Umno competed in alliance with the Penang Muslim League and helped them to win one seat out of nine, with most seats going to local left-wing parties: six to the Radical Party and one to the Labour Party with the other one going to an independent candidate. None of these parties, save for Umno, had much following outside of Penang, though the Labour Party did compete in Kuala Lumpur.

The Kuala Lumpur municipals was a different matter altogether, being pivotal in the story of our journey to independence. By then, Onn had already resigned from Umno mid-year and formed a new party, the Independence of Malaya Party (‘IMP’), and with it the British switched their preference to IMP rather than Umno – it should be understood that the British would rather work with Onn himself rather than Umno and so when Onn left Umno, Umno no longer became the preferred partner of the British.

IMP, Umno and MCA declared themselves contestants in the Kuala Lumpur elections. There was a somewhat post-communal outlook in this election not seen ever since. IMP was assumed to be the front-runner and they were already multi-racial while both Umno & MCA indicated that they were willing to field non-Malay and non-Chinese candidates respectively. The parties seem to understand that no race can rule Malaysia on its own.

Shifting alliances

IMP was initially the natural ally of MCA. The leaders of IMP and MCA, Onn and Cheng Lock respectively, were both favoured by the British, who were happy to broker the two Anglophiles to work together to formulate, discuss, propose and hopefully eventually execute British-friendly policies in a very British way. Cheng Lock, in fact, chaired the inaugural meeting of IMP on 16 September 1951, having himself previously called for formation of non-communal parties. If MCA had not already declared itself a political party earlier that year, it is possible that Cheng Lock could have been an IMP leader himself.

Onn instructed Thuraisingham to explore a possible IMP-MCA electoral pact but discussions proved to be rather difficult. This was largely due to Onn’s insistence that all MCA candidates would stand under the IMP banner. At that time, IMP was expected to win the election handily and I guess this gave them the clout to make such an outrageous demand. This did not sit well with the MCA leadership, though. MCA was set up to be the voice of the Chinese in Malaya whose implicit aim was the preservation of Chinese identity in what Malay nationalists then saw as a Malay nation. Asking such an organisation to be invisible is rather undiplomatic but then, diplomacy has never been Onn’s strong point.

Interesting point: the Malayan Indian Congress agreed to Onn’s terms and supported IMP for the election. So, MIC’s first foray into electoral politics was in opposition to Umno as was its first public action in opposing the Anglo-Umno constitutional renegotiation as part of PUTERA-AMCJA. So, unlike MCA which was set up after the PUTERA-AMCJA period and so never opposed Umno, MIC was in opposition to Umno for the first few years of its existence.

MCA preparations for the Kuala Lumpur municipal elections was led the head of Selangor MCA, H S Lee, instead of Cheng Lock, who was old and based in Malacca. Kuala Lumpur at that time was still part of the state of Selangor. Lee was a very successful businessman who was rather practical and impatient to get on with the work. There was a story that Lee was upset at not being seated with senior leaders at the IMP inaugural meeting but others noted Lee was more professional than that. Lee was probably already rather suspicious of Onn since the latter's support for the Immigration Ordinance 1950, which attempted to stop communist infiltration into Malaya by restricting movement of Chinese into the country, including those locally born. In fact, Lee was the one who alerted Cheng Lock's of Onn's stance. Whatever the story, Lee had little time for Onn’s petulance and was looking for other options.

Following the IMP-MCA failure to put together a pact, MCA put out a public statement on 3 January 1952, that non-Chinese interests should be adequately represented in the municipality. This was received very positively by Umno Kuala Lumpur and the next day, the chairman of its election committee, Yahya Razak, reached out to Ong Yoke Lin, his Victoria Institution ex-school mate, who was then a MCA member, to set up a meeting with Lee to discuss possible cooperation for the election. They met on 7 January and issued a signed statement the next day that Umno Kuala Lumpur and MCA Selangor will jointly contest the election.

There is a rather interesting story of that it was more a chance encounter in a coffee shop between Yahya and Yoke Lin, and the latter sat down to complain about Onn's behaviour over coffee. Whereupon, Yahya suggested he, Yahya, meet up with Yoke Lin's boss, leading to the Yahya-Lee meeting, and causing the dramatic break by MCA from IMP to Umno. I was, however, unable to find any corroboration for this story, sourced from Douglas Lee, who also ran in the municipal election and the son of HS Lee. Whatever the story, it is clear that Umno was MCA’s second choice for an electoral partner after IMP, even if MCA never had a formal pact with IMP.

Tunku Abdul Rahman, the president of Umno succeeding Onn, was very much publicly enthusiastic about the alliance as he was well aware that Umno on its own would make a little headway in the Chinese-majority Kuala Lumpur. Check Lock was rather more reserved, allowing MCA Selangor to make their own decisions but discreetly acknowledging his acceptance of the arrangement. He still retained close links with IMP and probably felt necessary to preserve options should the arrangements not work out.

The electoral pact was seen as temporary & local. Indeed, MCA members elsewhere continued to work with IMP, as some MCA members in Kuala Lumpur did for the municipal election, including Tan Siew Sin, Cheng Lock's son. Yahya also faced criticism for selling out the Malays and his division head resigned just days before the elections.

The alliance proved very a successful one as both Umno and MCA won the support of conservative Malays and Chinese in Kuala Lumpur. It gave Umno access to MCA funds from the business community while it gave MCA the Malayan sheen it needed. Twelve seats were up for grabs in the four wards of Kuala Lumpur and MCA ran in three of those wards & Umno one.

The results

The results saw the Umno-MCA pact sweeping three of the wards, leaving only Bangsar to the IMP. Umno and MCA comfortably won the Malay and Chinese areas of Sentul and Imbi respectively. MCA surprisingly won a landslide in Petaling, a new township where one would have expected the electorate to be more open to IMP’s more liberal ideas on non-communalism.

Bangsar was a much closer and a more interesting electoral battle. At that time, Bangsar was pretty much just what is now Jalan Bangsar and Brickfields. There was no housing estate then and Jalan Maarof was just a small rubber estate road. The electorate in Bangsar in 1952 included many Indians who worked at the railway station nearby. Brickfields at that time was very much the living quarters of those Indian workers. As such, Indian candidates had the edge in the elections and the IMP was able to capitalise on the popularity of Thuraisingam.

The IMP slate also included Devaki Krishnan the first Malayan woman elected to public office, who won by the narrowest majority in this election of 53 votes over an Umno candidate. She will later switch to MIC after the dissolution of the IMP. Another interesting candidate was Elsie Somasundram, an Indian candidate put up by MCA, who was well aware that you cannot win in Bangsar without an Indian candidate. As a result, she became the first and probably the only Indian to have run under the MCA electoral banner.

The successful alliance was quickly consolidated and Umno & MCA leaders later went on a nationwide tour to promote it. Cheng Lock took a bit more time but eventually endorsed a full break with the IMP. The Umno-MCA alliance spent the next three years deepening the alliance into every part of the country and forging a single electoral machinery with financing from the business community. That would be the next story.

Comments