Impact of culture & history on China's foreign policy - Part 1 Origins

- Jim Khong

- Jan 19, 2022

- 11 min read

Updated: Dec 21, 2022

China's recent rise has made many uncomfortable with its direction as a world power. The experience called China and its thinking are so very different to that in the West that misunderstanding is so easy, leading to unnecessary fear and unwarranted optimism. If Russia is a riddle in an enigma, China is even more mysterious, with little contact with Western history until lately, different religion & philosophy and even different basis for its language.

While I am not a scholar or an expert in the field, I find most analysis of China's foreign policy ignores the history and culture of this great nation and so I will attempt to explain how China's foreign policy is rooted in its history and its culture. The timeline of the Chinese dynasties here may help put things into historical perspective. Also, by culture, I do not mean the arts, although that is an element, but I mean the way people think and behave in the social sphere.

The article got much longer than I expected and is now part of a five-part series. In the process I all realised that what I really want to do is to share insights into Chinese culture, philosophy and practices, which shaped and are shaped by its history. Many non-Chinese observers view China as a mirror of their own experience but while there is much that the Chinese culture shares with the rest of the world, being part of the human world after all, there is also much that can be very alien to it. And of course, a great deal lies in the middle - same drives expressed in different conditions. So, I hope I can help the Western mind understand China using an examination of its foreign policy as a convenient vehicle. You will need to keep this intention in mind as this series is not intended to be a complete thesis of all the topics it touches on.

This is first article in the series. Impact of culture To understand China's power relationship with its neighbours, we have to delve into its culture shaped by its unique history. For more than two thousand years until the 19th century, China was the dominant culture in East Asia, a self-contained region bounded by frozen wasteland to the north, inhospitable deserts to the west, impenetrable mountains to the south and vast oceans to the east.

Pre-dynastic China some five thousand years ago was a patchwork of small kingdoms, most with its own language, cultural style, religion and social practice, some not even identifiably Chinese. Gradually the proto-Chinese civilisation in the Yellow river basin eventually absorbed all nearby cultures, subsuming them into a single recognisably Chinese culture. This integration found its culmination in the founding of the Chin dynasty by the infamous Shi Huangdi, who imposed a standard language script, weights measures & monetary systems and a single bureaucracy through its unitary political system. And that has been China ever since: stable dynasties punctuated by short violent interregna, with the Chin dynasty lending its name to the name by which the country is known in the West. This process of sinicisation eradicated many local identities, both prehistorical neolithic and protohistorical. The Baiyue (likely pre-Austronesian-speaking peoples in southern China whose Malayo-Polynesian descendants seafared all over South East Asia and the South Pacific via Taiwan), nomadic groups in the north and many hill tribes in the south are no more today. This process continues on to this day with the colonisation of Tibet and Xinjiang by dilution of the local indigenous population through Han Chinese immigration or by assimilation of the local indigenous cultures into the Han Chinese culture. Today, sinicisation assimilate not just nationalities but also religions as the regime attempts to subdue Christianity and Xinjiang Islam the way it sinicised Chinese Buddhism and Han Islam - be Chinese first the religionist second.

For almost all its entire written history of three and half thousand years, China have had the largest population in the world, larger even than the Roman Empire at its height. I believe the only time in history when there could be an empire somewhere else in the world with a larger population was (possibly) during the early Islamic empires before the fragmentation of Islamic dynasties, and during the Mongol empire. But these were not just short-lived (by the yardstick of China's dynasties), they were also highly diverse, unlike homogeneous China under a single dominant Han ethnic identity, culture, language and religion.

It was under the Han dynasty that a single unified Chinese national identity became accepted, as opposed to the enforced unification under the Chins. This is where we get the term Han Chinese. Under the Tang dynasty, the most cosmopolitan of the native Chinese dynasties, the Chinese culture was exported throughout Asia via trade and exchange of intellectuals. Imports that eventually became quintessentially Chinese as Buddhism (becoming identifiably Chinese syncretised with Chinese folk religion, Confucianism and Taoism) and rice (the Vietnamese variety was superior to the Chinese variety) were reversely introduced into China during these times. China first became a superpower under the Tang dynasty and to this day, tangren or Tang people is the colloquial term Chinese used for themselves.

Export of Chinese culture

With a unitary Chinese state, this dominance quickly expanded outside its borders to the east to Korea & Japan, and south to Vietnam. In these countries today, lunar new year is still being celebrated as is consumption of noodles amongst many other things, all of which are evidence of the Chinese influence (Ramen is Japanese transliteration of the Chinese La Mian). The influences of Chinese culture on the region on fields as diverse as cuisine, architecture, government polity, agriculture etc is just too numerous to list here. But for much of two millennia, the Japanese, Koreans and Vietnamese view of Chinese culture ranged from enthusiastic adoption to the occasional outright rejection but mostly, accommodation that Chinese culture was inevitable but did attempted to localise its features and forged their own respective independent identities - much like the way the way Canadians and Mexicans view American culture, but maybe even more so.

I find it says something of the dominance of the Chinese culture when Koreans and Japanese adopted Chinese characters in their written scripts even though their non-tonal-based languages were not suited for a script intended for the tonal-based Chinese language. The Koreans and Japanese later developed their own phonetic based scripts but even today, Koreans still supplement their hanjul alphabet script with hanja Chinese characters whereas Japanese is more like the Chinese-based kanji script supplemented by Japanese syllabic kana. Vietnamese did once used the Chinese script but switched to Roman alphabets under French rule.

Outside of the immediate orbit of the Chinese-based culture were basically barbarian lands. While, some Chinese influence can be seen throughout South East Asia, they are not the mainstay of local cultures and largely results from the voyages of Zhenghe during the Ming dynasty, a later Chinese period. Chinese then and to a much lesser extent now, considers peoples not exhibiting much Chinese influence as barbarians. Effectively, the Chinese view that for these nations progress would be by cultural sinicization much like the Japanese, Koreans and Vietnamese have achieved.

Chinese sinocentric attitudes to international trade Chinese historically have traded with the outside world but generally for non-essential items like animal fur or rare luxury items like glassware. The Chinese culture and economy were so self-sufficient that the Chinese considered that they had no need for imports. Still despite the occasional ineffectual total bans on outside trade, trade has always happened in Chinese history: just never on the scale that it occupy any part of the consciousness of ordinary Chinese in the streets, like it does for that nation of British shopkeepers. There is one significant exception: vast quantities of silver were needed for the Chinese currency during the Ming and Ching periods and this need to prop up an expanding economy through its silver-based currency had disastrous consequences for China and its psyche. The response of the Chinese emperor to the Macartney embassy in 1793 to open a permanent British trade mission is instructive:

"The Celestial Empire, ruling all within the four seas, simply concentrates on carrying out the affairs of Government properly ... We have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need of your country's manufactures, therefore O King, as regards to your request to send someone to remain at the capital, which it is not in harmony with the regulations of the Celestial Empire – we also feel very much that it is of no advantage to your country." (Oh, and it is important to note that the O King bit here is not an exaltation but more of a scorn or patronisation as the Emperor title was reserved for the Chinese Son of Heaven and King was very much everyone else. And the picture was really a British construct - the truth is that meeting Macartney was rather beneath the Emperor and they never met. When Manchu officials asked him to kowtow to a picture of the Emperor instead as is expected of lesser mortals, he refused, sealing the failure of the indolent British trade mission.)

While the Silk Road looms large in the thinking of people outside of China, it does not occupy the mind of the Chinese in a similar way. Chinese goods arriving in the outside world stirred more interest than outside goods coming into China, considering how self-sufficient China was. The story of the attention garnered by Caesar's appearance in Chinese silk had no equivalent in China, until maybe the arrival of Jesuit clocks. In Confucian thought, merchants do not have a high status as they were not deemed to be producers and as a result, the fruits of their labour in trade are not often not all that appreciated. The main imports into China via the Old Silk Road were not products but rather ideas on arts, fashion and the like, and just like Buddhism, ideas were easily sinicised until they became quintessentially Chinese, no longer foreign. Somehow, contributions from the outside to Chinese culture are often whitewashed and it is hard for the Chinese mind to understand that China had any dependence on the outside world.

There is one non-material commodity that China highly desired from the outside world, though: awe at its pre-eminence. The nation sees itself as the only civilised culture in the world, and was therefore the centre of the world. Literally. The name that the nation gave itself is translated as 'Middle Kingdom' but middle here have connotations of central or main, more than just geographical. Pre-Zhenghe Chinese world maps are largely of China occupying almost all the map with all its details while other known countries were pushed to the edges (yes, that is India at the extreme left in the map). Ricci told of the bafflement of the Chinese at the maps he initially introduced, which placed China on the extreme right that he reproduced a map with China in the centre.

This is what Chinese exceptionalism is based on: the belief that not only was China better than the rest of the world, it was the only civilisation in the world around which the world should revolve. It saw itself as the only country ruled by an emperor, Son of Heaven, with a heavenly mandate whereas all other nations are ruled by kings as mandated by the emperor. Japan's subversion of this principle has always irked the Chinese dynasties of old, just another element to the anti-Japanese antipathy in Chinese thinking. In many ways, Sino-centricism, fuelled by and in turn fuelling its isolationism exceed Euro-centricism in depth if not in breath.

Chinese relations with foreign cultures

As a result, the Chinese culture is basically xenophobic though not inherently racist. Chinese has always welcomed foreigners at the Chinese court who accepted Chinese culture (think Marco Polo and Matteo Ricci) and there seem to be no record of any personal racism that they encountered. Having said that, the fact that the emperors in Beijing at the time of the Jesuit missions after Ricci were not Han Chinese (they were Manchus, ie., foreigners who conquered China) probably had much to do with their acceptance of Western technology, eg., clocks, telescopes, that the Jesuits brought to the court. And Marco Polo arrived in Beijing at the time of the Yuan dynasty of Mongol emperors: again, non-Han Chinese. When faced with the self-evident superiority of the Chinese civilisation, foreigners are expected to learn in awe, not teach in arrogance. That is why I find the story of the Ricci missions all the more fascinating in their success in impressing the emperors and even got them to intervene in a Catholic doctrinal debate.

Here, I hasten to add that it is the culture that is xenophobic, not so much the people. Chinese migrants, freed from the direct influence of Chinese xenophobia, often assimilated and intermarried into the local culture within a generation or two: witness this in Thailand (two ethnic Chinese with Thai names were prime ministers), Philippines (ethnic Chinese with Filipino names have been cardinals) and in the West. There are exceptions of course, Malaysia being a prime example but there, the Chinese culture was deemed under threat with the oft-revived calls, among others, to abolish Chinese language education. So, maybe the Chinese can accept foreigners as long as they are not forced to give up their culture. Having said that, in Suharto Indonesia, Chinese culture was eradicated to a certain extent and for a short while but is now making a comeback.

China's treated other countries in the region as cultural offshoots or lesser cultures and by the Ming period was not able to conceive of equal status with other nations and cultures. Even Western science and technology that filtered into the Ming and Qing courts were considered to be of Chinese origins that the Chinese believed to be based on knowledge already understood in China but since lost, assuaging the hurt Chinese pride. Pride and face is overriding in Chinese culture.

Even today, colloquial Chinese slang would add a 'devil' epithet when describing non-Chinese peoples they do not like. Itis, of course not used in official language. The 'devil' epithet is most well-known in gweilo (literally devil person, a contraction of hungmaogwei or red hair devil) used for white men. This epithet is applied to all non-Chinese peoples, getting more widespread during times of tensions, arising from domestic politics or geopolitics. This epithet can change: Japanese normally carry the epithet for little boy (you can see how the Chinese view the relationship with lesser cultures here) but the devil epithet became more common with the Japanese invasions during WW2.

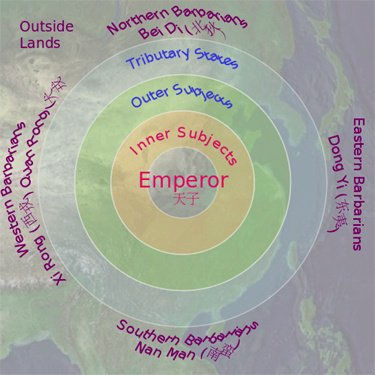

Also within the Chinese culture is the concept of tianxia literally all under heaven, where the entire human race under heaven is placed in concentric circles with the Chinese in the core, while tributary states and barbaric races occupied the more outward circles. The emperor is of course at the centre, surrounded by his court, nobility, ordinary Han Chinese, non-Han under Chinese rule in the outer circles, and the emperor-empowered ten thousand states outside of China in the outermost circle. This concept implicitly rather than explicitly forms the foundation of the Chinese worldview ever since the Han period, even under foreign Mongol, Manchu and European domination. The cultural weight of tianxia means China's ruling elite has never, even until today, accepted the Westphalia model of equal and independent nation-states.

For much of its history until the chaos of the late Qing dynasty in the 19th century and encroachment of European powers into South East Asia, Chinese people did not migrate to outside its borders in any significant numbers. While Chinese boats often plied the South China Sea, coming in contact with South East Asian peoples, there were few Chinese settlements in South East Asia, being limited to small isolated fishing communities & pirate bands and some itinerant traders - remember, there was relatively little demand for non-Chinese trade. In fact, the only Chinese colony arising from an official mission that I am aware of was sent in the dying days of the Yuan dynasty (Mongol emperors, non-Han Chinese) which was unexpectedly marooned in Borneo with the change of dynasty in China. This lack of interest created a vacuum in South East Asia, into which Indian traders filled, bringing with them Indian religion, language and culture - Malays throughout the region speaks a language with many recognisably Sanskrit loan words and were Hindus & Buddhists for longer than they were Muslims. I have to add that it seems that one of China's last influence on the region before the turmoil of the late Qing dynasty was the rejection by the Emperor of the name of Nam Viet preferred by the Vietnamese, reverting it to Vietnam today. (Can anyone help me confirm this?)

The next article in this series is here.

Comentarios